Selected Publications

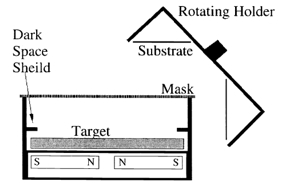

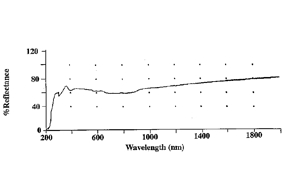

We report the preparation and structural characterization of lithium hydride and lithium fluoride thin films. These materials, due to their low absorption in the soft x-ray range, may have a role as spacer layers in multilayer mirrors. Theoretical reflection calculations suggest that an epitaxial crystalline multilayer stack of a nitride and a lithium compound spacer layer could produce respectable reflectance for short soft x-ray wavelengths (λ < 10 nm). Lithium targets were magnetron sputtered in the presence of hydrogen or ammonia to prepare the LiH films and nitrogen trifluoride to prepare the LiF films. The films were deposited on room temperature Si (100) or MgO (100) substrates. A near IR-Visible-UV spectrometer indicated a drop in reflectance at ~250 nm for a 100-nm-thick LiH film. This corresponds to a 5-eV band gap (characteristic of LiH). UV fluorescence indicated characteristic LiH defect bands at 2.5, 3.5, and 4.4 eV. The UV fluorescence characterization also indicated a possible lithium oxide (Li2O) contamination peak at 3.1 eV in some of our thin films. Film surface morphology, examined by scanning electron microscopy, appeared extremely rough. The roughness size varied with reactive gas pressure and the type of substrate surface. A LiH/MoN multilayer was constructed, but no significant d spacing peak was seen in a low angle CuKα XRD scan. It is believed that the roughness of the LiH film prevented smooth, uniform planar growth of the multilayer stack. Possible reasons of rough growth are briefly discussed.

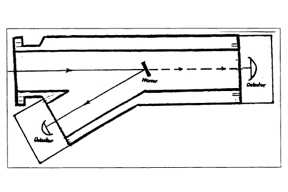

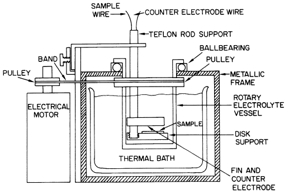

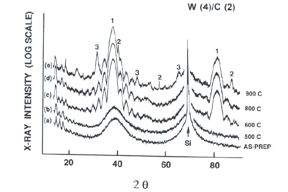

We report the effect that thermal annealing in inert and oxidizing atmospheres, and with and without encapsulating layers, has on the structure of tungsten/carbon [W/C] multilayer thin films. This study focuses on the tungsten component and deals mainly with multilayers where the ratio of thickness of tungsten layers is equal to or greater than for the carbon layers (that is, γ ≤ 0.5). This is in contrast to prior studies where the tungsten layer thickness was generally held constant and the carbon layer was varied. Thermal annealing in inert atmospheres produces reactions and other structural changes in the tungsten and carbide layers which depend on the as-deposited multilayer structure which depends, in turn, on the thickness of the tungsten layer. In samples where both the tungsten and carbide fractions of the multilayer are completely amorphous as deposited, which is the case for thin tungsten layers (thickness of tungsten (tw) < 4 nm/period), the reactions in the tungsten layer forming crystalline tungsten and tungsten carbide occur at annealing temperatures above 900°C. The layer pair spacing, or period, (d), in this group shows an expansion of up to 10–15% of the original value as has been reported in the past. Changes in both the tungsten and carbide layers, and their interfaces, contribute to changes in d spacing and relative thickness of the high and low Z components. When the tungsten layer thickness exceeds 4 nm per period the tungsten is partially crystallized in as-prepared samples. In such multilayers interfacial reactions, producing an oriented partially crystalline W2C/C superlattice, occur at temperatures of 600°C and below. The fact that W2C crystallites in one period can form a structure which is correlated to W2C crystallites in neighboring layers is somewhat surprising, since layers are presumably still separated by amorphous carbon which is still visible via Raman. The expansion of the layer pair spacing is relatively small (<5%) in this group and, more importantly, mostly involves increases in the thickness of the high Z components. Samples annealed in air at temperatures below 300°C are progressively destroyed by the oxidation of both tungsten and carbide layers. Encapsulation of similar multilayers with a thin (30 nm) dielectric layer of any of several types can retard oxidation to 600°C. The silicon-containing encapsulants generally perform better. Failure at this temperature is seen to occur from pinhole formation.